Night-time Window on Wildlife

,

Have you ever walked through some woodland and wondered what creatures might live there that we can’t see? That use their superb senses and camouflage to hide from human eyes and come out only when no-one is around.

Ever looked out into the garden, or the street and wondered what wildlife visits in the night? Maybe you’ve heard the scream of a fox, the hoot of an owl or the snuffling of a badger.

One way to find out is to throw a light switch or head out with a torch, but by doing so you might frighten off the animals you’d like to see, or at the very least change their behaviour hugely.

This is an issue that has always fascinated me, ever since hearing about the adventures of FW Champion, who in the 1920s developed some of the first camera traps – riding on elephant back and setting elaborate tripwires attached to cameras and flashlights to photograph tigers in the forests of India.

To our ancestors, darkness, a night lit only by the moon, the stars and perhaps a flicker of firelight was normal. It is easy to dismiss just how dark the world must have been before we had reliable, cheap, artificial light. For most of human history the night – and what went on beyond the reach of a candle was a mystery.

This led to more than a few misconceptions about animal behaviour. For example, it was a widely held belief all over the UK that hedgehogs ‘stole’ milk from cows during the night. To modern ears this sounds ridiculous, but it is a fact that hedgehogs are often found in cow pastures in the early morning… This belief was prevalent enough that a government bounty was placed on hedgehogs and millions were killed from the 16th to 19th centuries in exchange for a 4d reward per head.

If only there had been some way to see in the dark… we might have realised sooner that hedgehogs aren’t looking for milk in cow pastures – they’re foraging for insects in amongst the cow-pats!

It wasn’t just here that this ignorance of what went on in the depths of the dark night existed. In Africa observers noted every morning the lions lying regal amid the remains of their night-time prey – while shifty hyenas slunk around the edges of the kill site, looking for opportunities to dash in and grab a bite.

Noble, proud lions and cowardly, untrustworthy hyenas looking to steal other animals hard won food – how often have we seen that trope in books and films?

It wasn’t until the advent of first electric light, and then night vision systems, that naturalists realised we had got this almost exactly the wrong way around. In fact it is much more often the case that the hyenas do the hard work, hunting efficiently and intelligently as a pack to bring down prey animals – only to have the bigger, more powerful lions move in and ‘steal’ the kill after the hard work is done.

So what other wildlife secrets are out there in the night, waiting to be discovered?

The first thing you discover about camera traps are that they’re expensive. A basic model from one of the big established names in the field can cost £150. And on top of that you’ll need batteries, an SD card, and probably most importantly, a security chain or box to prevent your £150 camera disappearing.

The second thing you discover about camera traps is they’re not very reliable. Of the three traps bought for a project here a couple of years ago none are still working.

But what if there was another option?

Inspired by my love of small gadgets that beep and blink flashing lights I had recently acquired a Raspberry Pi minicomputer. The Raspberry Pi is a British computing phenomenon. Designed to encourage people to take up coding it’s the biggest selling British computer of all time and can be found powering projects ranging from media centres in people’s homes, to automatically closing the doors on chicken coops at dusk, to taking photographs from the edge of space.

The cheapest version of the Raspberry Pi is £4. A night vision camera and infra-red lights to attach to it can be had for £15. A micro SD card is £3 and the whole thing can be run off a mobile phone battery…

And so the TurboMegaCameraTron 4000 was born.

A quick raid through the kitchen found an old ice cream tub (it had been carelessly left in the freezer filled with ice cream); two minutes work with a pen knife (don’t copy this at home kids) made some holes for the lens. All I needed then was a plaster for my cut finger and I had a rudimentary waterproof case suitable for mounting the Raspberry Pi itself. Yeah that sound you hear is the corporate world of professional camera trap manufacturers quaking in their boots!

So I had a bunch of parts in an ice cream tub. What next? A computer is useless without software, so the next step was to do some research on how exactly to run a camera system. I have a little bit of background in computer programming – just enough to know that I’m no good at it. Luckily however you don’t need to know what you’re doing… There’s a great community of builders and modders out there, using a Raspberry Pi to run all sorts of weird and wonderful gadgets, schemes and devices. Quite a few people have set their Pi up to run home security or monitoring systems, which do a similar job to a trailcam – triggering a camera when they see movement. It didn’t take long to locate something suitable and tweak it for my purposes.

I was ready to go – all I needed now was some wildlife! I had suspected for some time the presence of mice in my garden so I stuck the camera out in a likely looking spot and, tempted by some peanuts, I soon had footage of a family of mice living the high life.

Another feature of the system I chose means that the Pi can broadcast live images of what it is seeing to a computer, tablet, or smartphone if it has a WiFi signal – the antics of the local mice were better than anything on TV.

Within a week of having the camera out filming mice we got our first sighting of something more interesting – a fleeting image of a fast moving creature right at the edge of the camera’s infra-red light range. This was tantalising stuff, it was clearly a large creature but even frame by frame analysis of the film wouldn’t quite reveal what it was…

But I had suspicions! My next move was to source a large plastic storage box, and get to work with my trusty penknife again. One plaster later I had a home-made mammal feeding station. A carefully sized square hole in the side (taped over to cover up any sharp bits) means that small mammals can get in to the box but inquisitive cats can’t! The box was duly placed out in the garden, along with some peanuts, mealworms, cat biscuits and some water. All we had to do now was wait…

Though not for very long. Within 15 minutes of me putting the box out for the first time it had its first occupant! (This happened so quickly that I actually didn’t notice. Unhappy with the initial location of the box I went out and repositioned it – the watching trailcam picked up the footage of me moving the box, complete with its spiky occupant, which appeared unphased by its impromptu aerial journey. I had no idea anything had happened until I reviewed the footage the next morning – and I’ve never really lived it down).

But at least we had proof of the identity of our mysterious visitor… Using night vision camera traps I had proven the existence of hedgehogs in my back garden! Another great advancement for science.

And so the camera project idea started to take shape.

Day to day my time in Cumbernauld is spent working on the Wild Ways Well project, a partnership between Cumbernauld Living Landscape, The Scottish Wildlife Trust and The Conservation Volunteers.

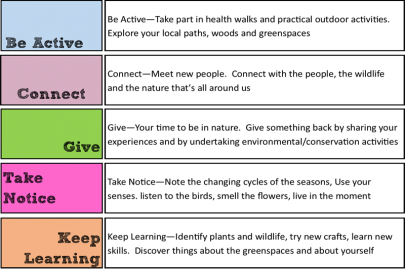

Wild Ways Well intends to demonstrate the fact that spending time outdoors, amongst nature, is beneficial to everyone’s mental wellbeing. As part of this we take people suffering from, or at risk of, mental health problems (ie anybody and everybody) out into the greenspaces of Cumbernauld to undertake wildlife and conservation themed activities, all built around the structure of the Five Ways to Wellbeing – the framework for good mental health which is used by the NHS and the major UK mental health charities.

Building and operating a wildlife camera trap fits into these five ways very well.

Finding good places to situate a trap means you have to Be Active and get out into the parks, woods and reserves looking for potential wildlife hotspots. One drawback of our camera traps is that they only have limited battery life so every couple of days the traps have to be inspected to swap batteries.

In order to get great film footage of wildlife the users would really have to Take Notice of the clues that visiting animals leave behind. Searching for badger holes, deer beds, fox trails, scratching posts, foraging areas and nestholes.

Everyone involved would Keep Learning in a variety of ways. By filming at night we learned about animals that live around us, sharing our town, which we rarely see. A lot of the footage we collected – especially in the early days, was unusable as we slowly built up our skills, learning what works, and what doesn’t.

We could Connect with the wildlife we filmed, and with the ecosystem that supports them. It is possible after a while to identify individuals amongst the regulars who visit the trap. We can also connect with the wide community of camera trappers out there across the world.

Finally, by sharing what we found we can Give pleasure to others and give everyone an insight into the wonderful world of wildlife that lives around us after dark.

One final change we made was to the case we used to keep the electronic components safe. The ice cream tub case works well as temporary solution but it still left the Pi in some danger of getting wet or damaged.

Luckily another solution was found, in the shape of Cumbernauld’s Men’s Shed.

Supported by Cumbernauld Action for the Care of the Elderly (CACE), Men’s Shed is a brilliant organisation that gives men a place to feel at home and pursue practical interests in the company of other like-minded people. With the use of a workshop in Cumbernauld, complete with a full array of tools and materials, the guys can spend their time practicing old skills and learning new ones. Creating, restoring, repairing and renovating—all with a brew, a biscuit and a chat never far away.

The benefits of a Men’s Shed are obvious, it encourages learning, skill sharing, community, achievement and social interaction. It allows people, who may have no other outlet for their skills and creativity, to take part in something positive and productive, to learn new skills, connect with other people, and share knowledge and experience.

As well as all these ‘invisible’ benefits there are also the tangible end products that can be produced.

The guys at the Cumbernauld shed took on the brief of making a housing for the Raspberry Pi camera trap and came up with a range of ingenious ideas all designed to keep the Pi safe and dry while maximising the chance of filming wildlife.

One of the first designs they prototyped was the ‘tunnel’ trap. This unit encloses the electronics in a long wooden tunnel (many small mammals love to explore tunnels). The structure not only keeps the electronics and bait dry but it makes sure that the camera films only creatures which enter the tunnel—meaning the batteries will last longer and it can be safely placed in sensitive areas like school grounds without inadvertently filming people. It also doubles as a footprint tunnel!

Another design was the ‘bird box’ this was much more convenient to move around and much easier to place unobtrusively.

With the help of the Wild Ways Well group, St Maurice’s High School pupils and Cumbernauld Living Landscape volunteers these camera traps were placed in the parks and wildlife reserves of Cumbernauld to see what creatures share our greenspaces with us.

We recorded hours of HD video which we condensed down into a short film to demonstrate that Cumbernauld isn’t just a great place for people to live.

While our cameras were out they caught footage of foxes, hedgehogs, rabbits, squirrels, woodpeckers, deer, birds of all descriptions, mice, voles, badgers and more.

Wildlife thrives here too.

Thanks to The Scottish Wildlife Trust; The Conservation Volunteers; CACE; Men’s Shed; Health and Social Care North Lanarkshire.