A secret winter larder on our doorsteps

,

Early November. The days are getting shorter, the yellowing leaves are nearly down, and even the grass is beginning to die back. It’s nearly winter. Yet out for a walk on a sunny day I still spot a bee or two, and a red admiral butterfly darts past looking pretty chipper. They’ve obviously discovered a source of food, despite the lateness of the year.

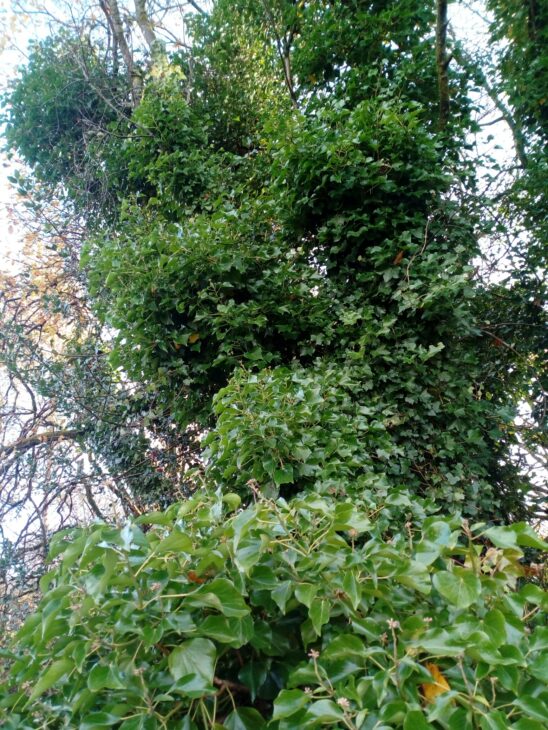

I suspect that what they may have found is ivy. It’s one of our latest flowering plants – often blooming well into November. You have to look closely to notice the flowers though. Unlike many of the blousy wildflowers of summer, ivy’s flowers are a subtle yellowy green, tucked in among its evergreen leaves. Despite its coy display, it can support around 50 species of wildlife. While the invertebrates love its nectar and pollen, its inky berries, high in fat, appear in the depths of winter, a welcome late meal for berry-eating birds like thrushes and blackbirds.

Ivy is our only native liana – the kind of plant we usually associate with jungles in the tropics. And though it loves to climb up trees, over walls, along fences, it is actually just as happy spreading across the ground. While it’s true the weight of the climber can sometimes pull down old or diseased trees, it seldom kills the plant – and can sometimes actually protect it. The shady framework it creates is ideal nesting habitat for birds, or hiding places for hedgehogs.

And in the past even people found it useful. Its berries made a pinky-purple dye; a concoction of its leaves and vinegar was used to cure corns (please don’t try this at home!); and unmarried girls pinned three ivy leaves to their nightdresses at All Hallows Eve to make them dream of their future husbands (you can try that if you like!)

Next time you’re out for a stroll take a look at that ivy patch you’ve always walked past – there’s more to it than meets the eye!